For decades, China harshly restricted the number of babies that women could have. Now it is encouraging them to have more. It is not going well. With an aging population and a rapidly shrinking labor force, more children were vital if the country was going to maintain economic growth.

That’s why, at the end of 2015, the one-child policy became the two-child policy—prompting eager anticipation of a baby boom in state media.

That boom never appeared. There’s a simple reason why: The cost of raising a child in China is at an all-time high and getting more expensive; doubling or tripling that budget is an insurmountable task for many. It’s a common pattern in developed countries, where birthrates fell even without government pressure.

Reversal of a Policy of the Old People’s Republic

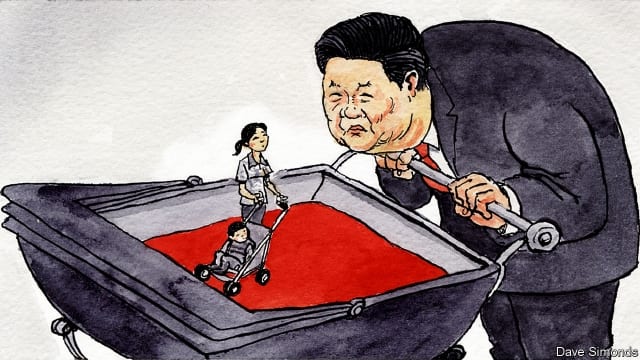

Officials are now scrambling to devise ways to stimulate a baby boom, worried that a looming demographic crisis could imperil economic growth — and undercut the ruling Communist Party and its leader, Xi Jinping.

It is a startling reversal for the party, which only a short time ago imposed punishing fines on most couples who had more than one child and compelled hundreds of millions of Chinese women to have abortions or undergo sterilization operations.

The new campaign has raised fear that China may go from one invasive extreme to another in getting women to have more children. Some provinces are already tightening access to abortion or making it more difficult to get divorced.

Experts say the government has little choice but to encourage more births. China — the world’s most populous nation with more than 1.4 billion people — is aging quickly, with a smaller work force left to support a growing elderly population that is living longer. Some provinces have already reported difficulties meeting pension payments.

Unforseen Consequences of Modernity

It is unclear whether lifting the two-child limit now will make much of a difference. As in many countries, educated women in Chinese cities are postponing childbirth as they pursue careers. Young couples are also struggling with economic pressures, including rising housing and education costs.

The “pro-life” stance in China will not be modeled after the Christian-led model in the West, but the moralizing and objectification of women’s bodies will be extremely similar. Rather than focusing on the sanctity of unborn life, eugenics and traditional family values will make up two essential pillars of future Chinese natalist policies. This means “high quality” Han children produced in a legitimate marriage are the only ones the state is interested in, and unmarried pregnant women will face coercion to marry or to abort.

Freely-chosen abortion will be increasingly regulated, with hurdles such as spousal approval, doctor’s approval, mandatory hesitation periods, and required counseling. It is likely that students will soon receive more directed sex education, with clear messaging on abstinence until marriage and optimal birthing age for more intelligent offspring. In short, the government’s strong grip on governing fertility will remain unchanged.