Another former Guantanamo Bay prison detainee is back to his old ways.

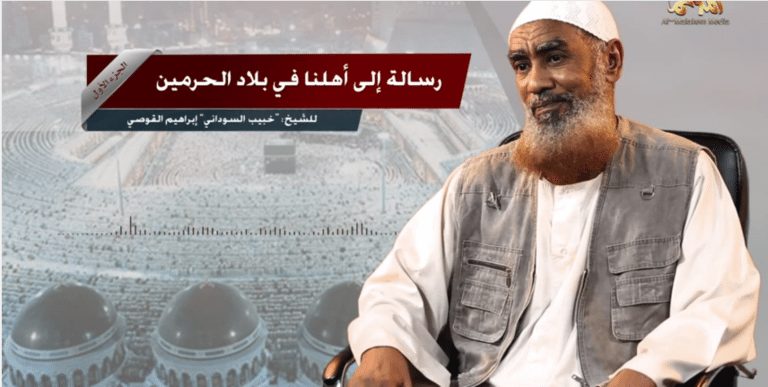

Ibrahim al Qosi, who was released in 2012, has resurfaced in numerous propaganda videos for Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

Qosi is an experienced Al Qaeda fighter who served as Osama Bin Laden’s body guard. His latest APAQ video was published on Feb. 6 and spans two parts.

The nearly 50-minute video is titled “A Message to Our People in the Land of the Two Holy Mosques.” It was translated by The Long War Journal, a publication dedicated to documenting the War on Terror.

In the video, Qosi refers to what he calls the “blessed” 9/11 attacks, and the American campaign against a “worldwide community of Muslims.” He also calls for the fall of Saudi Arabia and criticizes the Kingdom’s allegiance to the United States. Qosi says Bin Laden was influenced by the U.S. “occupation” of the country’s two holiest sites. He also attacks Saudi Arabia’s opposition to the “mujahedeen in Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen.”

The video ends with Qosi calling on youth to join APAQ in Yemen.

In July 2010, Qosi plead guilty to charges of conspiracy and material support for terrorism. By cooperating with prosecutors, he was given a suspended sentence to spend two more years at Gitmo.

In 2012, he was sent to his native Sudan.

According to legal documents and memos prepared by intelligence and military personnel at Gitmo, Qosi joined Al Qaeda in 1990. He received extensive weapons training at the infamous Farouq training camp in Afghanistan. In 1994, he joined Bin Laden’s personal security team. In 1995, he waged jihad in Chechnya before returning to Bin Laden in Afghanistan.

Qosi then fought alongside the Taliban, according to a leaked Joint Task Force Guantanamo threat assessment (JTF-GTMO).

The document states that “From 1998 to 2001, al Qosi traveled back and forth between the front lines near Kabul and Kandahar to help with the fight against the Northern Alliance.”

Qosi was finally captured by Pakistani authorities in Dec. 2001 after fleeing the Battle of Tora Bora, when the U.S. and its allies bombed the mountains where they believed Bin Laden was hiding.

Qosi spent the next decade locked up at Gitmo.

Following Qosi’s release in 2012, his lawyer Paul Reichler said Qosi planned to live peacefully for the rest of his life in Sudan.

Last December, he began re-emerging in AQAP videos describing himself as a senior leader of the group.

That month, Reichler told the Miami Herald he had not heard from his former client since his release.

“I was told by a Sudanese lawyer a year ago that al Qosi was working as a taxi driver in Khartoum,” Reichler told the newspaper in an email. “I have received no information about his activities since then, and I do not know what he has been doing, or where he is living.”

In 2003, investigators asked Qosi why he remained loyal to Bin Laden as long as he did.

According to The Long War Journal, Qosi cited his “religious duty to defend Islam and fulfill the obligation of jihad and that the war between America and al Qaeda is a war between Islam and aggression of the infidels.”

According to the JTF-GTMO document, Qosi in 2007 was deemed a “high” risk to the US and its allies. President Barack Obama in December stated only “low-level” operatives are released from Gitmo.

It’s not clear whether Qosi is fighting alongside terror groups again. That’s not the case for other prisoners released from Gitmo.

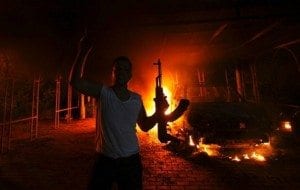

Abu Sufain Bin Quam was released in 2007 and returned to Libya. He joined the terror group Ansar al-Sharia and climbed its ranks. The group later led deadly attacks on the US Consulate and CIA facilities in Benghazi on September 11, 2012. The attacks killed four Americans.

Said Mohammad Alim Shah was repatriated to Afghanistan in 2004. There, he kidnapped two Chinese engineers and claimed responsibility for a hotel bombing before launching a suicide attack in 2007. That attack killed 21 people.

Abdullah Ghoffor was also released in 2004. He returned to Afghanistan where he became a high-ranking Taliban commander. He led attacks against U.S. and Afghan troops before being killed in a raid.

According to a March 2015 memo released by the office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), more than 100 of the 600 prisoners released from Gitmo since it opened were “confirmed” to have reengaged in extremist activity. About 70 others are suspected of doing so.

The gitmo prison population stands at 107 with 17 in the process of being released, according to DNI.

The majority of released prisoners left their cells under the Administration of former President George W. Bush. In recent weeks, however, the Obama administration has been vamping up its efforts to squeeze the prison population with the intention of closing it.

Not all prisoners leaving the cells of gitmo simply return home. Many are placed under the jurisdiction of authorities in other countries. Still, these authorities aren’t always capable of preventing ex prisoners from pursuing terrorist activity, especially in countries where extremist groups have influence.

Most released detainees are returning to conflict-ridden countries with terrorist strongholds. Qosi’s case is no different. Sudan is home to several extremist rebel groups.

Nonetheless, statistics show the number of released prisoners returning to “extremist activity” is relatively low.

Those numbers could be much higher depending on what is defined as “extremist activity.”

Although Qosi is a hardened Al Qaeda fighter with years of experience on the battlefield, AQAP might think he now serves a better post in front of the camera.

Ryan Mauro, national security analyst with the Clarion project, explains.

“Current arguments over terrorist recidivism upon release from Gitmo vary based on what it means to rejoin the terrorist cause,” Mauro tells Fox News. “The rate is lower if you only consider those who went back to physical fighting and it is higher if you include those who rejoined terrorist groups. But we often miss another factor: What about those who use their rock star status to radicalize without engaging in violence? We must remember this is an ideological war.”

[adinserter block=”2″]

[adinserter block=”7″]